Have you ever been scolded for waking up late or staying up too long at night?

Well, I don’t know about you, but I’ve lost count of how many times my parents have lectured me about my “messed up” sleep schedule. No matter how hard I try to fix it, I somehow end up being wide awake when the world sleeps and struggling to get up when it’s time to start the day.

Sounds familiar?

Here’s the twist – it turns out, it might not even be your fault.

The reason you stay up late or struggle to follow a “normal” sleep routine could be written in your genes. Yep, and there is an actual biological term for it – circadian rhythm.

Relax, let me explain the term for you.

Key Topics:

What is circadian rhythm?

Your circadian rhythm is the pattern your body follows based on a 24-hour day — it’s the name given to your body’s internal clock. This rhythm tells your body when to sleep and when to wake up, and for some people, that clock just runs on a slightly different schedule.

And no, this isn’t just some random internet theory– it’s backed by real science.

Circadian rhythms are regulated by light, behavior and a biological clock mechanism– a set of ‘clock genes’ located in cells throughout the body.

Your body sets your circadian rhythm naturally, guided by your brain. But external factors, like light, can affect the rhythm, too. For example, when light enters your eye, cells send a message to your brain that it can stop producing melatonin (a hormone that helps you sleep).

Your circadian rhythm connects to an internal clock in your brain. This internal clock is located in a tiny cluster of cells known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The SCN is in a part of your brain called the hypothalamus. Throughout the day, internal clock genes in the SCN send signals to control the activity throughout your body.

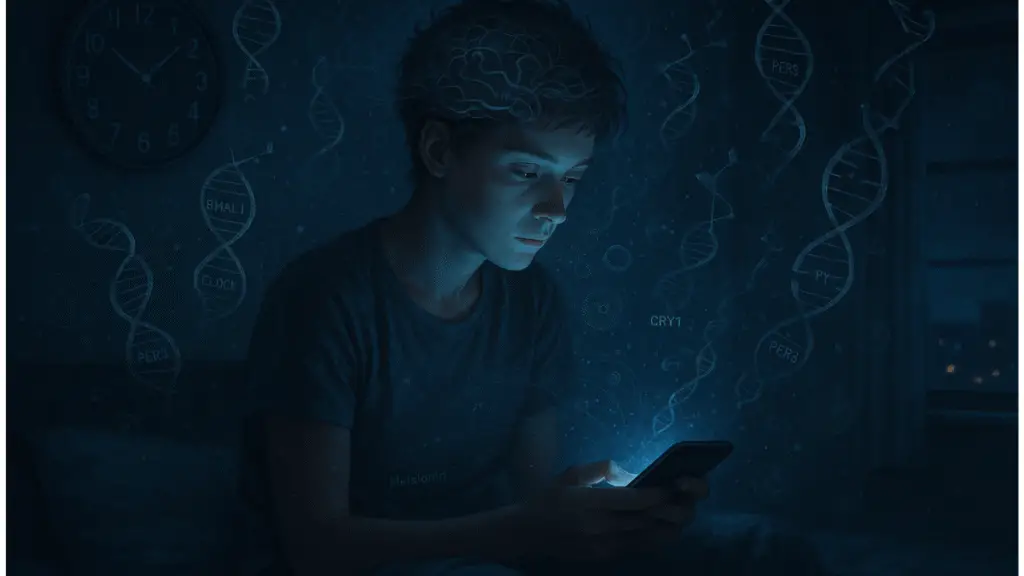

There are specific genes in your genome – BMAL1/BMAL2, CLOCK, CRY1/CRY2, and PER1/PER2/PER3 – that regulate and control the transcription and translation.

Expression of these core clock genes inside the cell influences many signaling pathways, which allows the cells to identify the time of day and perform appropriate functions.

Or, in a simpler way, these genes help in regulating your circadian rhythm, sending signals that tell your brain when it’s time to sleep, wake up, eat or even focus.

Now, when there’s a mutation or variation in these genes, your body may run faster, slower, or just differently from most people. That’s why someone might feel completely alert at midnight but struggle to open their eyes at 7 a.m. – even after a full night’s sleep.

In fact, research published in the Sleep (2003) by Archer et al. showed a clear genetic link. They found that people who are homozygous for the shorter PER3 variant (4 repeats instead of 5) were significantly more likely to be night owls or suffer from delayed sleep phase disorder (DSPD)– meaning they simply could not fall asleep early, even if they are tired.

This is just not it– you will be even more surprised when I tell you that this internal cycle does not tick the same way for everyone.

In babies and toddlers:

Newborns typically don’t develop a circadian rhythm until they are a few months old. That’s why their sleep pattern is so erratic. Babies usually start to produce and release melatonin when they’re about 3 months old.

Cortisol development occurs between the 2nd and 9th months. Once toddlers develop a circadian rhythm, they have a pretty regular sleep schedule.

In teenagers:

During our teen years, this rhythm usually shifts later, which is why most of us were wide awake at 2 a.m. during our high school and college days.

In adults:

As we grow older, the clock shifts again– older adults often feel sleepy earlier in the evening and wake up earlier in the morning.

Although apart from our genes, our lifestyle choices also play an important role in this, like how much light you get during the day, your caffeine intake, late–night screen time, or even your eating schedule, can all influence your circadian rhythm.

A study that took place in Harvard Medical School in the summer of 2018 also mentions that scrolling on smartphones before bed can interfere with our circadian rhythm.

A researcher and her colleagues found that repeated evening use of a light-emitting tablet suppresses the release of the sleep-promoting hormone melatonin and shifts the circadian clock later, delaying bedtime and reducing alertness the next morning.

Adjusting the brightness and color tones on e-devices may minimize these effects.

Wrapping up:

So, the next time someone calls you lazy for sleeping or staying up late, remember– it might not be a bad habit, it’s just your biology and a pattern shaped by your genes.

And while we all try to follow society’s strict 9-to-5 routine, it’s time we start recognizing that not everybody is the same.

Share this article, subscribe to Genetic Education and never miss any updates.

Resources:

Archer SN, Robilliard DL, Skene DJ, et al. A length polymorphism in the circadian clock gene Per3 is linked to delayed sleep phase syndrome and extreme diurnal preference. Sleep. 2003;26(4):413-415. doi:10.1093/sleep/26.4.41.

Reddy S, Reddy V, Sharma S. Physiology, Circadian Rhythm. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519507/.