“Genetic mutation(s) cause cancer. Explore the basics of cancer genetics and understand how genetic factors contribute to cancer.”

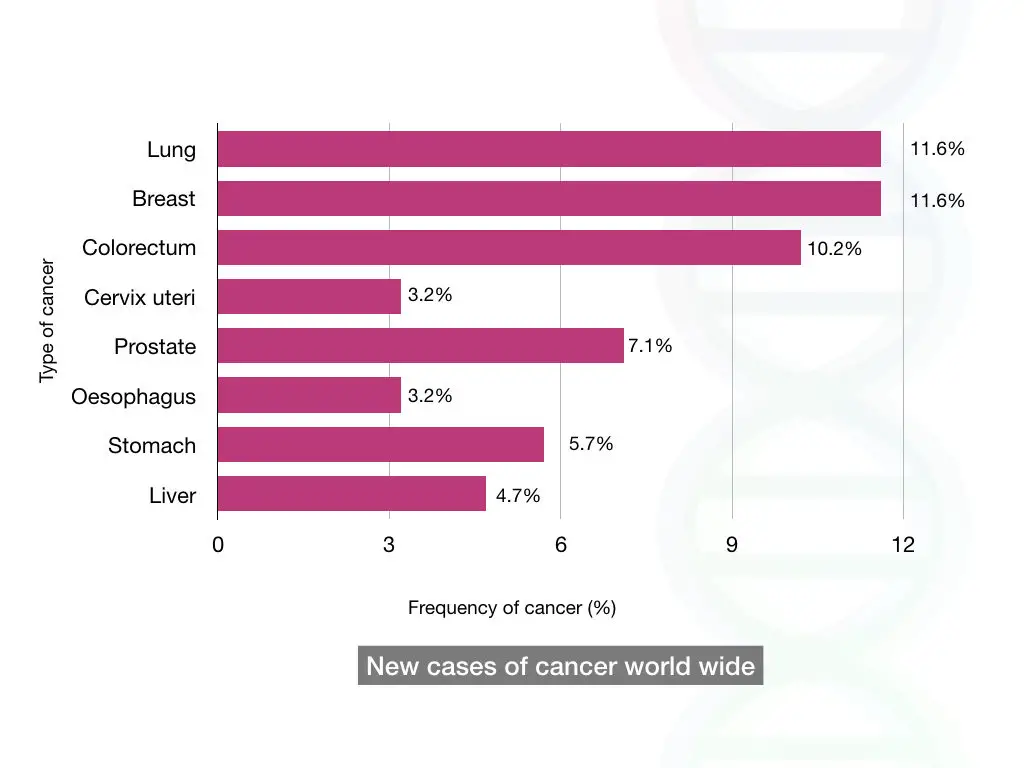

- Cancer is the second most common cause of death worldwide.

- >300 candidate genes are well-studied in cancer

- 1% of human genes contribute to cancer

- 70 Genes are associated with germline cancer, while 320 genes are associated with somatic cancer.

- Genetic mutations cause 95% of cancers.

Cancer is an extremely complex condition. A cellular error— cancer with compound molecular mechanisms and cellular pathways results in serious and “near” lethal phenotypes.

Not nearly, but all cancer has a definite and clear genetic origin. It’s now known that genetic or epigenetic alterations result in varied degrees of cellular carcinoma.

However, due to its complex nature, lengthy terminologies and the involvement of many mechanisms make it difficult for students or any novice to understand cancer genetics.

This article is an honest effort to explain the genetics of cancer. We explained the common concept, genetic mechanism and common genes involved in cancer.

Related article: Genetics vs Epigenetics: From Gene Alterations to Gene Expression.

Stay tuned.

Disclaimer: The content presented herein has been compiled from reputable, peer-reviewed sources and is presented in an easy to understand manner for better comprehension. A complete list of sources is provided after the article for reference.

Key Topics:

What is cancer?

Let’s start with the cell cycle. We will not comprehensively understand all things, but for better understanding and to lay the foundation for this article, we will look at the broader concept.

So, a cell’s primitive function is to divide and form daughter cells. By doing so, it forms tissues, organs and systems. The genetic material replicates and distributes into the daughter cells.

The genetic material is inherited from cell to cell by this mechanism. Once a cell is done with its function or is damaged, it undergoes apoptosis— we know it as programmed cell death. Because it’s programmed, it can not produce any inflammatory responses.

So, in conclusion, a cell replicates “faithfully” and copies all the genetic material, divides into daughter cells and meets apoptosis. Meaning, it is destined for death. Cancer occurs when cells become immortal.

Got the point!

No?

Allow me to explain.

Any sudden change in the present cellular system will disrupt the whole process. Consequently, a cell can’t reach its destination— apoptosis. It divides, infinite times, without any restrictions or boundaries.

This is known as “Cancer.”

“Cancer is referred to as an uncontrolled and infinite cell growth and division due to genetic mutations.”

The condition becomes even worse when it invades the original tissue into the surrounding ones and becomes potent enough to spread to distant body parts. Hence, a few common features of cancer are,

- Uncontrolled cell division

- Lack of apoptosis

- Spreading to other tissues (metastasis)

Now, moving further and understanding the molecular mechanism of how cancer occurs?

How does cancer occur?

Cancer occurs due to genetic mutation(s). When a gene mutates, it slips its control over the cellular differentiation process. Not all, but more than 300 genes with over 1% of human genes contribute to cancer.

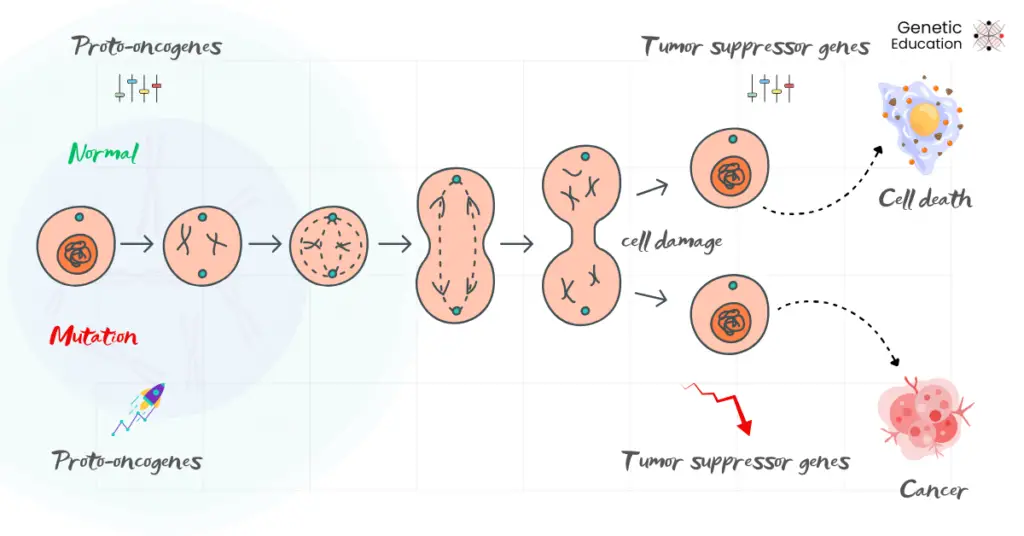

The entire process, from cell replication and differentiation to apoptosis, is tightly regulated by a set of genes. Proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes are this class of genes.

Both categories, all together, have entirely opposite functions, but their fine balance controls the cellular proliferation activity. Proto-oncogenes promote cellular differentiation whereas tumor suppressor genes suppress the proliferation.

In addition, the system is backed by DNA repair genes, which are always trying hard to repair all the sudden or unwanted DNA damage to fine-tune the process. We will discuss cancer-causing genes separately.

Furthermore, cell cycle checkpoints ensure proper cell division and repair.

Cancer originates when an imbalance occurs in this system.

The overactivity of oncogenes (the mutated counterpart of the proto-oncogenes) and under or lost activity of tumor suppressor genes, or failed DNA damage response, can’t arrest cells for apoptosis.

Resultantly, the faulty or mutated cells divide infinitely, invade the tissue or can spread to distant organs. This condition has serious health-associated and lethal consequences, which we know as cancer.

Now, you may have a question: How does the imbalance occur?

Genetic mutations, either SNP, indels, CNV, translocation, or inversion at the molecular or chromosomal level, in any of these genes fail to perform their ‘category-specific’ function and cause tumors.

For instance, mutations in the TP53 gene– a candidate (tumor suppressor) gene, and “Guardian of our genome” fail to stop the multiplication of damaged or mutated cells.

Curious about cancer-causing genes? Let’s jump into the next and crucial segment of this article.

Cancer-causing genes:

Scientists believe that approximately 3000 human genes are directly or indirectly involved in cancer, however, >300 genes are well-studied and established as candidate genes.

Put simply, genes having either a direct or indirect role in tumorigenesis are referred to as cancer-causing genes. They are divided into three broad categories: proto-oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and DNA repair genes.

Remember our objective!

To simplify the concept for beginners and students, we will not make this segment review-heavy but rather express it with a simpler understanding.

Proto-oncogenes:

“They are the promoters.”

Proto-oncogene are the set of genes that promote cell growth and division, which is essential for the normal cell cycle. RET, MET, CDK4+, RAS, MYC, EGFR, etc are the types of proto-oncogenes.

The table below shows examples of some proto-oncogenes and their function.

| Proto-oncogene | Location | Function | Cancer |

| RET | 10q11.21 | Tyrosine kinase receptor, cell survival | Thyroid cancer, MEN syndromes |

| MET | 7q21-31 | Growth factor receptor, cell migration | Lung, gastric, renal cancer |

| CDK4 | 12q13-14 | Cell cycle regulator (G1-S transition) | Melanoma, glioblastoma, sarcoma |

| RAS-family | 12p12, 11p15, 1p13 | Signal transduction, cell growth | Lung, colorectal, pancreatic cancer |

| MYC | 8q24.21 | Transcription factor, cell proliferation | Burkitt’s lymphoma, breast, lung cancer |

| EGFR | 7p11.2 | Growth factor receptor, cell survival | Lung, glioblastoma, head & neck cancer |

40 different proto-oncogenes have been reported to date. The mutant counterparts of the proto-oncogenes, the oncogenes are dominant. The gain of function mutations in these genes reduces the apoptotic activity and increases the cell division rate.

Gain of function mutations

A mutation that overactivates the mutant gene copy, often leading to increased protein function, prolonged activity, or activation in inappropriate conditions.

Now, the question is, which type of mutations produce or convert proto-oncogenes to oncogenes?

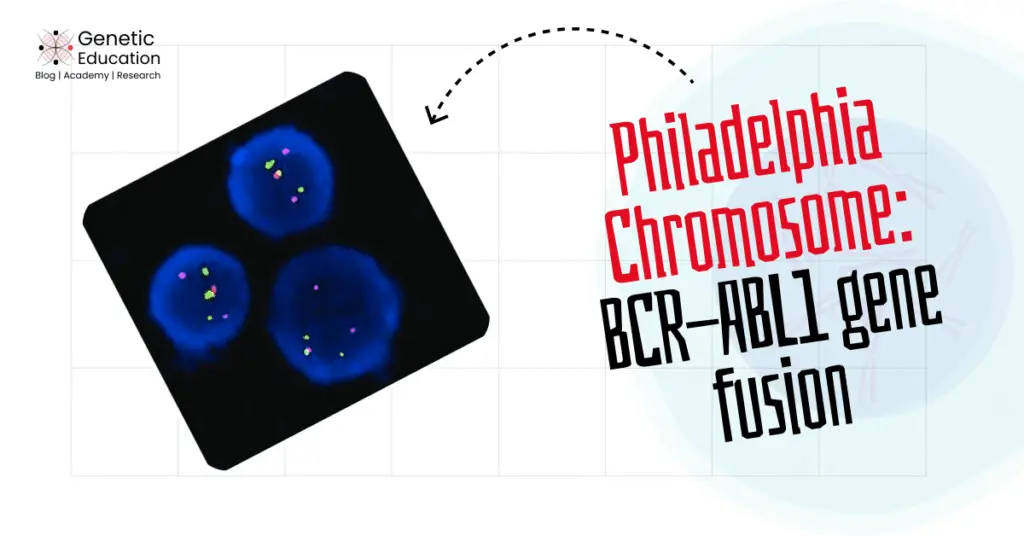

SNPs, indels, CNVs, chromosomal translocations, gene amplification, and gene fusion are common mutations that produce gain-of-function type mutations and convert proto-oncogenes into oncogenes.

Examples of different gain of function mutations in proto-oncogene and their cancer types.

| GOF mutation | Gene | Cancer type |

| SNP | KRAS | Lung, Colorectal, Pancreatic Cancer |

| Indels | EGFR | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) |

| CNVs | MYC | Breast Cancer, Lung Cancer |

| Chromosomal translocation | BCR-ABL | Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) |

| Gene amplification | HER2 | Breast cancer |

| Gene fusion | RET/PTC | Thyroid cancer |

Note that mutations in the proto-oncogene promoter also convert them into oncogenes and induce tumorigenesis. We will discuss various types of mutations in detail in another separate article.

Furthermore, studies showed that several proto-oncogenes are exclusively active only during the embryogenesis stage. It helps faster fetal growth by high cell division activities.

It switches off and becomes inactive after birth. Activation of such proto-oncogenes at any stage of life induces oncogenic activity. Moreover, previous studies also showed viral-mediated oncogene activation.

Oncogenes are the most common genes majorly involved in various types of cancer.

Tumor suppressor genes:

“They are the defenders.”

As the name suggests, tumor suppressor genes are a set of genes that suppress the cell division activity and induce apoptosis. Common examples of TS genes are TP53, APC, MEN1, NF1/2, and BRCA1/2, etc.

The table below shows common TS genes, their chromosomal location, function and involvement in cancer.

| TS gene | Location | Function | Cancer |

| TP53 | 17p13.1 | Regulates cell cycle, DNA repair, apoptosis | Most cancers (breast, lung, colon, etc.) |

| RB1 | 13q14.2 | Controls cell cycle progression | Retinoblastoma, Osteosarcoma |

| BRCA1/2 | 17q21 and 13q12.3 | DNA repair, genomic stability | Breast, Ovarian Cancer |

| APC | 5q21 | Regulates Wnt signaling, prevents uncontrolled cell growth | Colorectal Cancer (FAP) |

| PTEN | 10q23.31 | Regulates cell growth, survival pathways | Prostate, Endometrial, Glioblastoma |

| NF1 | 17q11.2 | Regulates Ras signaling, prevents uncontrolled growth | Neurofibromatosis Type 1, Glioma |

In total, ~1217 human tumor suppressor genes are reported to date. Two crucial functions of TS genes are to prevent cell division and arrest cells for apoptosis. So, technically, it reduces the tumor progression by providing cell death signals.

However, loss-of-function mutations in TS genes lead to tumors.

Loss of function mutations

When mutations lead to loss of gene function or fail to synthesize the protein.

Studies reported that tumor suppressor gene mutations follow a recessive pattern of inheritance. Meaning, a single mutant and LOF copy is not sufficient for tumorigenesis. Tumor suppressor gene-mediated tumorigenesis is a bit complex and tricky.

The reason is! The single mutant allele can not directly cause cancer unless the second allele mutates. This can be explained by the two-hit theory proposed by Alfred Knudson.

The first hit or mutation occurs during either the germline or somatic stage. If it is germline in origin, it inherits. In both cases, the individual is predisposed to cancer but doesn’t get it.

The cancer happens only when the second hit occurs— the second allele mutates, leading to a complete loss of function condition for the tumor suppressor gene. The condition is known as loss of heterozygosity.

Common mutations reported in tumor suppressor genes are microdeletions, missense and nonsense mutations and point mutations causing frame-shifts. Notably, chromosomal translocations are rarely reported.

| Mutation | TS gene | Cancer |

| Point mutation | TP53 | Many cancers (e.g., breast, lung, colon) |

| Nonsense mutation | RB1 | Retinoblastoma |

| Frameshift mutation | BRCA1 | Breast and ovarian cancer |

| Large deletion | APC | Colorectal cancer (FAP) |

| LOH | VHL | Renal cell carcinoma |

| Promoter hypermethylation | MLH1 | Lynch syndrome (colorectal cancer) |

Epigenetic modifications like promoter hypermethylation also inactivate the allele completely during the second hit and lead to tumorigenesis.

Related article: Proto-oncogenes vs Tumor Suppressor Genes- Key Differences.

DNA repair pathway genes

Cell division is a complex, highly regulated and controlled process. However, it can make mistakes, even in normal conditions. Fortunately, our cells’ DNA repair pathway, comprising many genes, repairs these errors.

During every replication cycle, thousands to millions of nucleotides can be wrongly incorporated, resulting in the wrong genetic code. However, a specialized gene toolkit– the DNA repair machinery repairs such random errors immediately and, if not, forces the cell to apoptosis.

By doing so, it regulates cell division, differentiation and apoptosis. Mutations in DNA repair genes also fail to perform cellular maintenance and cause cancer.

Where BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the common DNA repair genes, MLH1, PMS2, ATM, ATR, XPA, etc. are other genes in this category. Note that different genes follow different DNA repair pathways.

The table below shows various DNA repair genes, their functions and their role in cancer.

| DR gene | Function | Cancer |

| BRCA1 | Homologous recombination repair | Breast, and ovarian cancer |

| BRCA2 | Homologous recombination repair | Breast, ovarian,and prostate cancer |

| MLH1 | DNA mismatch repair | Colorectal, endometrial cancer (Lynch syndrome) |

| MSH2 | DNA mismatch repair | Colorectal, gastric cancer (Lynch syndrome) |

| ATM | DNA double-stranded break repair | Breast, leukemia, lymphoma |

| XPA | Nucleotide excision repair | Skin cancer |

Types of Cancer:

Cancer can be inherited or sporadic, and based on that, three types of cancer are– hereditary cancer, familial cancer and sporadic cancer. Keep in mind, here, hereditary and familial cancer are different.

Hereditary cancer:

Cancer is genetic but not hereditary all the time. Roughly 5 to 10% of cancers belong to this category. In this condition, a mutant cancer allele is inherited from either the father or mother, or both, to the child.

Pedigree analysis can reveal the inheritance pattern between generations. A common checklist for hereditary cancer is early cancer onset, multiple family members having the same cancer type. It also affects multiple body parts.

It follows the classic Mendelian inheritance pattern but usually follows autosomal dominant inheritance. For example, hereditary breast or ovarian cancer and hereditary Lynch syndrome.

Familial cancer

Familial cancer is slightly different from hereditary cancer. In this condition, the cancer is not inherited, but instead, it is present in many individuals of a family. Meaning, a particular cancer occurs in the family more often than expected.

For instance, familial stomach cancer, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), etc. Keep in mind that cancer doesn’t necessarily follow a Mendelian inheritance pattern.

Sporadic cancer:

Sporadic cancer, often known as somatic cancer, is a condition that occurs in the somatic cells or during any stage of life after birth. 90% of cancer belongs to this category.

Sporadic cancer occurs by genetic mutations, though the environment plays a significant role. For instance, individuals with tobacco addiction have a higher chance of acquiring cancer at any life stage.

In another example, individuals living at an extremely high temperature are likely to have skin cancer. In both these cases, tobacco addiction and an extremely high temperature are the environmental factors that induce sporadic cancer.

It neither follows any inheritance pattern nor has any family history. In addition, other family members or the next generations may lack the genetic predisposition for the cancer. In conclusion, it is only limited to the individual and the tissue or organ affected.

Some of the common environmental factors that contribute to sporadic cancer are pollution and pollutants, bad lifestyle, tobacco addiction, carcinogens, radiation, etc.

Keynotes on sporadic cancer:

- Occur to anyone at any stage of life, even after birth. Usually occurs at the late onset of age.

- Not inherited

- Not familial

- Involves environmental factors

- Doesn’t have any predisposition

- Restricted to the individual only

- Can spread to other tissues

| Hereditary cancer | Familial cancer | Sporadic cancer |

| Inherited gene mutation | Genetic + environmental factors | Random mutations + Environmental factors |

| Germline | Somatic/ germline | Somatic |

| Passed through generations | No clear pattern | Not inherited |

| Early age of onset | Middle age of onset | Usually later in life |

| Multiple affected generations | Clusters in families | No strong history |

| Inherited BRCA1/BRCA2 breast cancer | Colon cancer in the family | Most lung and skin cancers |

Complex cancer genetics

So, isn’t that enough?

Either loss-of-function or gain-of-function, or both types of mutations, when occurring, in germline or somatic cells, cause cancer!

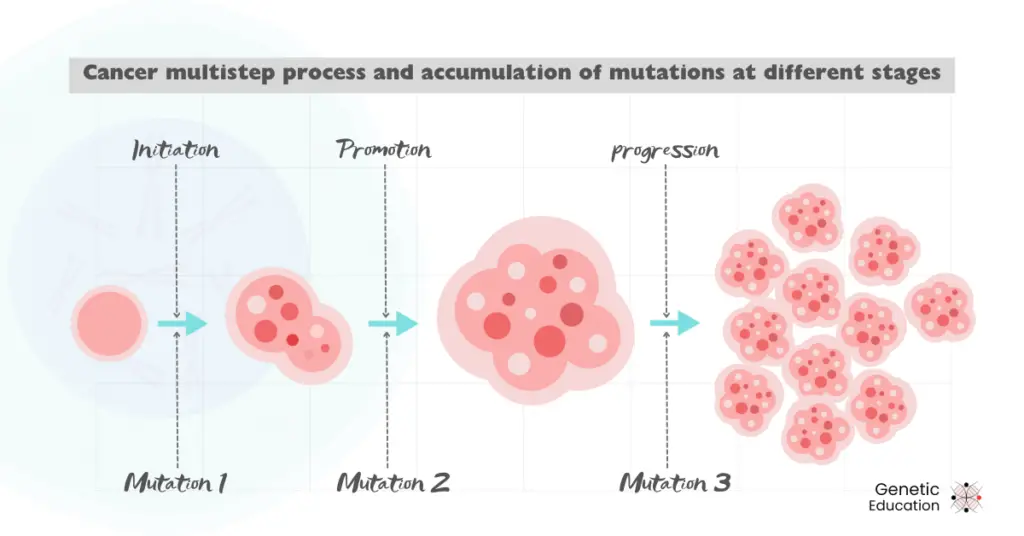

The cell cycle is a multistep process, and so is cancer! It involves complex molecular pathways and many genes. The complexity has been of many folds as genes are interdependent on other genes’ activity.

This means that mutations within a single gene certainly influence the activities of other genes and start disrupting the cell cycle. At different stages, different gene and/or chromosomal mutations occur.

The accumulation of more and more mutant genotypes makes the phenotype even worse.

It may be like that.

For instance, a mutation fails the DNA repair pathway in “some” progenitor cells, and a tumor is initiated. As a result, if it fails to repair the mutations in proto-oncogenes, the tumor progresses.

Now, more genes mutate, and the tumor spreads readily and so on; due to this, the associated phenotypes become worse and worse. This makes therapy and drug development against a particular cancer challenging.

This is just for your understanding.

Wrapping up:

Scientific research and reviews clearly show that cancer is caused by genetic factors or mutations. However, lifestyle and environmental factors also play a significantly important role.

Mutations in proto-oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes or DNA repair genes have been extensively involved in causing cancer, though there are >300 genes that can induce tumorigenesis.

Cancer is a complex and multi-step process. Various genetic tests help not only in research but also in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. In the next article, we will discuss the genetic techniques used in cancer.

I hope you like this article, share it and subscribe to Genetic Education.

Resources:

- Chial, H. (2008). Proto-oncogenes to Oncogenes to Cancer | Learn Science at Scitable.

- Retrieved from Nature.com website:

- https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/proto-oncogenes-to-oncogenes-to-cancer-883/.

- Lee, E. Y. H. P., & Muller, W. J. (2010). Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressor Genes. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 2(10), a003236–a003236. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a003236.

- Chow, A. Y. (2010). Cell Cycle Control, Oncogenes, Tumor Suppressors | Learn Science at Scitable. Retrieved from www.nature.com website: https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/cell-cycle-control-by-oncogenes-and-tumor-14191459/.

- Oláh, E. (2005). Basic Concepts of Cancer: Genomic Determination. EJIFCC, 16(2), 10. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6008968/.