Taste is an acquired trait! The biggest myth we all believe in.

When we talk about taste, we often think of it as being shaped by habit, culture, or the food we grew up eating. Some people love coffee, while others find it bitter; some cannot resist sweets, while others prefer savoury.

It feels like preference alone, but science tells us that our sense of taste is not just acquired but is also genetic.

Yes, taste is hidden within our genome, and our genes decide how strongly we perceive the Umami flavour of grilled mushrooms, the bitterness of coffee, sweetness or sourness.

For instance, some people who are extremely sensitive to bitter compounds, while others find it common, is because of variation in genes.

Let’s understand the genetics behind taste.

Read more: Is Eye Color Genetic?

Key Topics:

What is taste?

Taste is one of our primary senses, which helps us identify the flavours of the food and drinks we consume. Basically, we feel the taste when the chemical perception of certain molecules interacts with our tongue.

The five primary taste aspects that the human tongue can identify are umami (savoury), sweet, salty, sour, and bitter.

In combination, these flavours help us make conscious food choices, alert us to potentially dangerous substances (such as toxins, which are often indicated by bitterness), and make sure we are getting the nutrients we need to survive.

How do we sense taste?

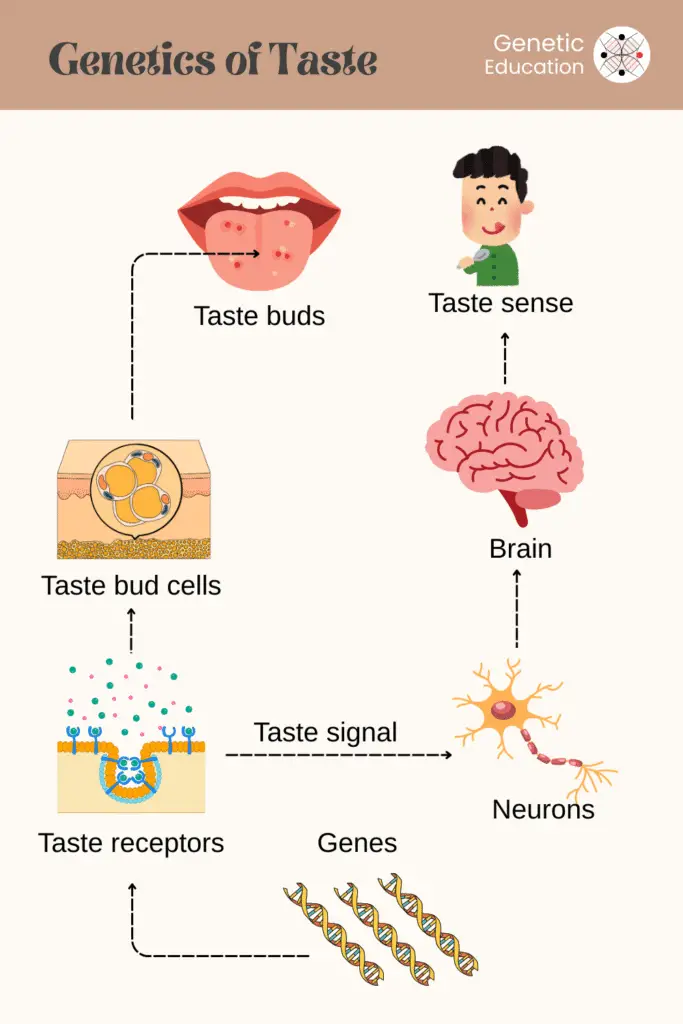

Taste is a preliminary sense by the specialized cells present on our tongue. Papillae are the tiny bumps on our tongue that hold clusters of cells known as taste buds. These taste buds contain special receptor cells to detect different flavor molecules through the receptors

Hence, when it finds a specific taste molecule, the receptor activates. For instance, salt particles activate salty receptors, while sugar molecules trigger sweet receptors.

The food we eat interacts with the receptor cells inside our taste buds. And these receptors are basically the proteins, each specialised to detect a certain kind of taste.

These receptor proteins are encoded by specific genes in our DNA, and this is where genetics steps in. When a gene is expressed for the particular taste receptor, that’s when we identify the taste.

When these receptors are stimulated, they send electrical signals through nerves to the brain. The signals are then recognised by the brain, and this allows us to recognise and enjoy the flavors of the different varieties of foods we eat.

Genetics of Taste:

Our taste buds carry specialised receptors to detect sour, sweet, salty, bitter and umami flavours. Now, there are various genes in our genome that determine a specific or set of tastes, alone or in combination with other genes.

A few common genes for various taste receptors are TAS2R1, TAS2R2, TAS2R3 and SCNN1A and SCNN1B. Check out the table to know more.

| Gene | Taste perception | Note |

| TAS1R2 + TAS1R3 | Sweet | These two genes work together to form the sweet receptor, allowing detection of sugars and artificial sweeteners. |

| TAS1R1 + TAS1R3 | Umami | Detects glutamate and other amino acids, responsible for the savory taste in foods like soy sauce or mushrooms. |

| ENaC ( Epithelial Sodium Channel genes, e.g., SCNN1A, SCNN1B, SCNN1G) | Salty | These encode sodium channels that allow detection of saltiness by directly sensing sodium ions. |

| TAS2R family (e.g., TAS2R38) | Bitter | Large family of genes; TAS2R38 in particular is linked to strong or weak sensitivity to bitter compounds (like in broccoli, Brussels sprouts, coffee). |

| PKD2L1 | Sour | Involved in sensing acidic (sour) tastes by detecting hydrogen ions. |

Nevertheless, differences in particular genes determine how strongly or weakly we perceive these tastes. For instance, TAS1R genes are involved in the detection of sweet and umami flavours, whereas genes in the TAS2R family manage sensitivity to bitterness.

However, studies suggest that single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), a genetic variation, can alter an individual’s taste perception.

This explains why two people may have quite different reactions to the same food—for example, one person may find broccoli to be extremely bitter, while another person may find it to be enjoyable.

Similar to this, some people have more functional taste receptor genes, making them “supertasters,” who have heightened taste sensitivity, while others are “non-tasters,” who have milder flavour perception.

All these trait variants occur because of the different variants of the taste genes.

Let’s have a close look at some recent research to understand the genetics of taste more scientifically.

A systematic review of 103 human studies published in the Journal of Frontiers in Genetics found consistent evidence that genetic variation largely explains why people perceive and prefer flavours differently.

The most accurately associated locus is the bitter-taste receptor TAS2R38 (three linked SNPs: rs713598, rs1726866, and rs10246939), that largely determines whether a compound is “taster” or “non-taster” for substances like PTC/PROP (two synthetic compounds that scientists use to test bitter taste sensitivity) and affects preferences for bitter vegetables, coffee, and some alcoholic beverages.

A growing, yet less reliable, set of associations for sweet and umami receptors (TAS1R2/TAS1R3) and signalling genes like GNAT3 are also obvious results, as are CD36 variants (e.g., rs1761667) associated with fat taste sensitivity.

The review also notes that heritability estimates are moderate for sweet perception and high for some bitter measures (e.g., PROP/PTC), highlighting the fact that a large portion of our palette is shaped by genetics rather than just culture or habit.

This research clearly shows that receptor variants can also influence our food choices and thereby our overall health.

For example, people who are highly sensitive to bitterness may not eat certain vegetables like broccoli or Brussels sprouts, while the non-tasters might consume them normally.

This evidence shows us that taste is both biological and behavioural, and how variation in a single gene can significantly shape our perception of taste. And this perception can directly influence our nutrition and lifestyle.

Another study showed the same, but for the sweet taste. Sweet taste is not only influenced by lifestyle but also by TAS1R2 gene variations.

The focus of this study was on the TAS1R2 gene, which encodes the receptor that is responsible for detecting sweet molecules. The sweet perception is found to be altered by a specific variant in the TAS1R2 gene.

It was reported that people with the wild type version of the gene had stronger sweet taste perception, a greater liking for sweet foods and even showed dietary differences such as higher fibre intake but lower levels of HDL cholesterol.

The present study has been conducted on 2500 participants and using the genome-wide association study. The study also showed that the RGS9 genetic locus is linked to decreased sweet preference.

Is taste inherited?

Yes, taste is an inherited trait. Since the taste receptors are proteins encoded by specific genes, any variation in these genes can be passed from one generation to another.

However, as we discussed, it isn’t solely genetic, so our lifestyle and environment also shape our taste preferences. And as it is a multigenic trait, it is difficult to determine a specific inheritance pattern for the taste in general or for various taste preferences.

Taste epigenetic:

Taste itself is a complex genetic trait, as we already discussed it involves not only genes but also the environment. For instance, our parents, family or regional food habits, our lifestyle, even financial status, all these factors collectively shape gene variants that decide our taste preferences.

Related article: What is Gene-Environment Interaction?- A Beginner’s Guide.

Wrapping up:

Taste is believed to be a behavioural trait, but it is partially. Now, you know that taste is also largely influenced by our genetics. There are specific genes that influence how we perceive the sweet, bitter, salty, and other flavours. Variations in these genes shape how strongly we respond to certain foods.

So next time, when someone forces you to eat something, tell them, it doesn’t suit your genes! Share this article and subscribe to Genetic Education.

Resources:

- Bachmanov, Alexander, et al. “Genetics of Taste Receptors.” Current Pharmaceutical Design, vol. 20, no. 16, 31 May 2014, pp. 2669–2683, https://doi.org/10.2174/13816128113199990566.

- Diószegi, Judit, et al. “Genetic Background of Taste Perception, Taste Preferences, and Its Nutritional Implications: A Systematic Review.” Frontiers in Genetics, vol. 10, no. 1272, 2019, p. 1272, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31921309, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.01272.

- Stevens, Harry, et al. “The Genetics of Sweet Taste: Perception, Feeding Behaviours, and Health.” The 14th European Nutrition Conference FENS 2023, 19 Feb. 2024, p. 342, www.mdpi.com/2504-3900/91/1/342, https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2023091342. Accessed 15 Sept. 2025.